The Great Whernside Cloudburst of July 20, 2014

The

pages below are under development and will be updated on a regular

basis.

All images are from the author's collection unless otherwise indicated.

Click on images for larger view: use back arrow to return from image view.

Great Whernside (704m, 2316ft) from Elslack Moor, September 22, 2012.

On the afternoon of Sunday July 20, 2014 we had parked at Black Park – the high point of the road between Eastby and Barden - for a brief scramble around the rocks with Patrick and Thomas when the skies to the north over Grassington Moor seemed to darken, then blacken, although no thunder or lightning was observed. Quite clearly a major weather event was about to take place and this was mentioned at the time. It was not until an email came from John Cordingley on Monday 21st, that the story started to be revealed. John had been at Park Rash earlier in the day and he had observed that a major flood had taken place within the previous 24 hours or so. He thought that the flood pulse came mainly through Dow Cave rather than down the gill.

The adjacent photograph was taken at 1405h on the 20th. This was a fine warm sunny afternoon when the background to the centre and right of the picture should be showing the easterly part of Great Whernside and an extensive panorama of Grassington Moor.

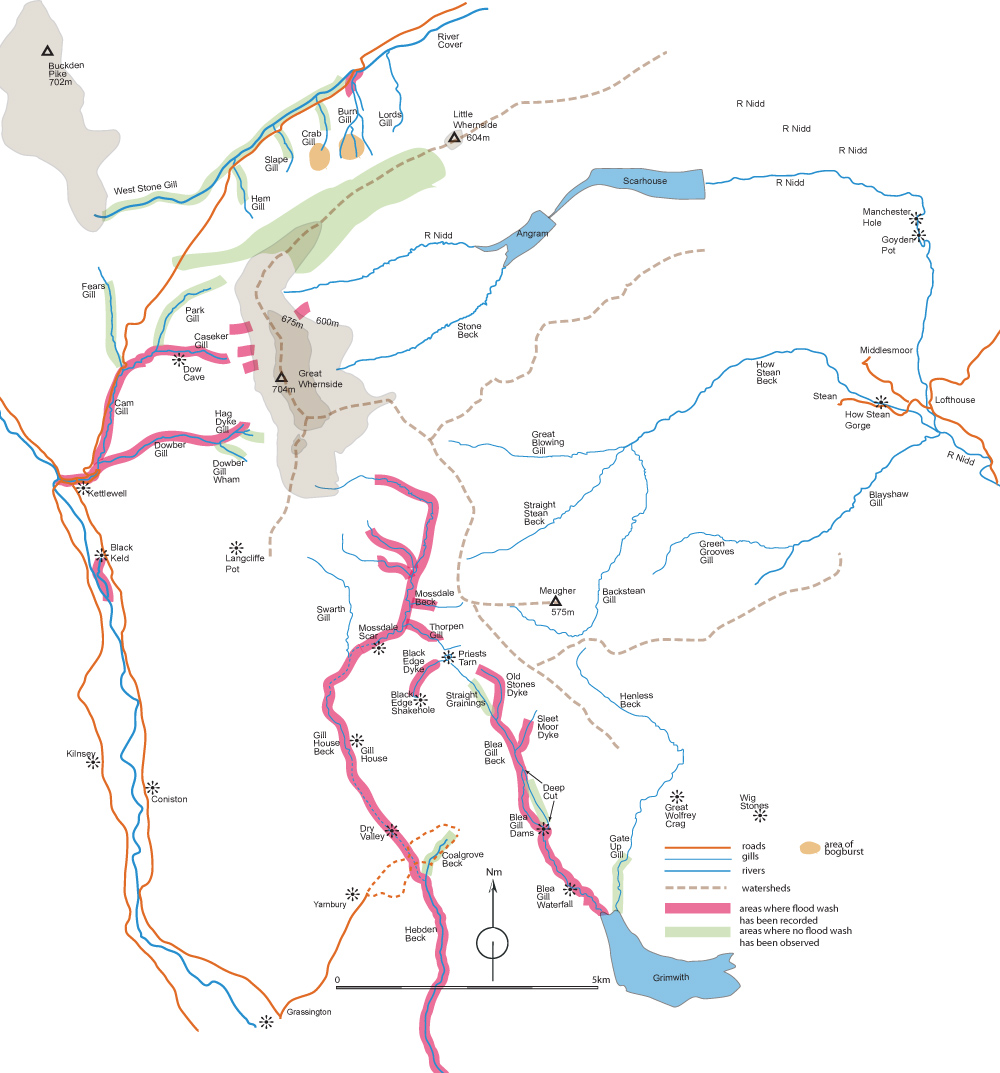

An enormous cloudburst seems to have occurred over Great Whernside and the upper reaches of Conistone Moor creating huge floods down Mossdale, Thorpengill, Gill House, Dry Valley, Dowber Gill, Caseker Gill, Coverdale and, seemingly, How Stean. The locations recorded to date are indicated on the sketch map below and depicted photographically in the following sections.

More information came to light when Maud and I called on Clifford Lambert and also when we met up with Robert Lambert of Mile House on Sunday September 14 and again on Sunday October 19. It transpired that a massive flood had passed through Kettlewell on the afternoon of July 20. Great torrents of water had also passed down Mossdale Beck, down Caseker Gill and down Dowber Gill.

According to Clifford Lambert the beck swept through the village and overflowed all the bridges. He went up on the fells to view the effects of the flood and found that he stonework around Providence Pot entrance had been washed away leaving only the concreted parts intact. In Caseker Gill, the scar (Caseker Crag) had great gulleys washed out down it.

Robert Lambert had lost at least a dozen or more sheep and lambs washed away by the flood. A more accurate figure would be known after the late October roundup. He had seen a flood line 30 feet high on Mossdale Scar. Robert had seen that the flood waters came through to Black Keld inside a couple of hours, rather than the twelve hours or more usually estimated by water tests, and waters came out almost as liquid mud. The flood was not seen at Mile House. Farmer Walmsley of Grassington had seen two black clouds meeting on Great Whernside with clear sky between shortly before the event. Farmer Richard Appleton was up on the high ground above Kettlewell when he spotted what he thought were a line of people against the scarp of Great Whernside. Through his binoculars what he actually saw was a series of cascades falling off the tops. He knew this was serious and drove back down to Kettlewell on his quad as fast as he could because there were youngsters playing in the river. He got them away from the river and shortly afterwards a wall of water came down the beck through the village. According to Anna Craven in the village, the storm cloud remained on the hill top for two hours.

On the weekend of October 18-19, 2014, Edward Whitaker spoke to a lady resident in Kettlewell who lived near the beck and she talked of hearing a strange noise on a fine dry Sunday, July 20th. She looked out so see a great muddy flood overflowing the banks of the beck at the top of the village. It remained in flood for some four hours.

Jan Brownson and Nigel Easton had been walking on Great Whernside at the time all this started up. Jan said it was quite horrendous. They saw a line of streams cascading off Great Whernside as they fled off the moor down to Kettlewell getting well and truly soaked on the way.

This event also had some effects in Nidderdale which could have had possible grave consequence for the Nidderdale caves. According to Alan Butterfield, a lady he knew in Pateley Bridge had two caravans near the river. On that day, July 20, a fine summer day, and without warning, the river rose alarmingly to the extent that it lifted one of the caravans a foot or more off the ground. However it seems likely in this case that the flood came down from the How Stean catchment.

* * * * * * * *

From the pages of the: North Yorkshire Advertiser of July 23:

Some people in Coverdale said the rain on Sunday night had been so heavy that it was difficult to stand up - it was “monsoon rain” apparently.

This extremely intense rain caused a number of peat landslides and avalanches which ran off to either side of the hills - into the River Cover in Wensleydale, a tributary of the River Ure and into a tributary of the River Wharfe above Kettlewell in Wharfedale.

* * * * * * * *

Another source from an internet browser: Landslides at Coverhead Estate, Sunday 20 July 2014:

Survey of landslides, Saturday 9 August 2014 – Brief comments for the landowners

There was abundant evidence of enormous volumes of water on the slopes at the time of the landslides, indicated by the extents of peat debris runout and, in one place, an ‘eruption’ of pressurised water from within a natural pipe within the clay that blew out the clay cover …. Other pipes were found in the head of one of the landslides ….. It is clear that the excessive rainfall was the trigger for the landslides, and that the failure processes were entirely natural and similar to other landslides elsewhere in recent years. ….. the head of the landslide (around 4000 m3 volume) ….. (Dr Alan Dykes 11 August 2014)

Sketch map of the Great Whernside area

Based in part on the 1848 OS 6 inch County series Sheet 116 with locations determined by GPS (Garmin 62s).

Click on the map for larger view: use back arrow to return to normal view.

The Yarnbury Dry Valley and the Mossdale catchment

Images from the author's collection September 17 and October 22, 2014.

On September 17, 2014, Dave Milner, Mike Squirrel and myself walked from Yarnbury up the Dry Valley, by Gill House and as far as Mossdale to have a look at the effects of the cloudburst in that area. There was ample evidence that a huge river had travelled down the valley at some speed shifting massive amounts of rocks, soil and peat.

Right: This image was the first and very striking effect we spotted where great quantities of floodwash had accumulated on the remains of a washed-away wire fence where the moor road crosses the Dry Valley.

Left: Mike and Dave examine a strand line on the bank near Fossil Pot that shows the flood to have been some 4m wide and perhaps 1.5m deep

Right: a little further along the Dry Valley a great mass of boulders had accumulated in a shallow valley but again the flood level can be seen from the strand line to have been some 5-6m wide and perhaps 1m deep..

Left: A major earth and rock moving excercise had been brought into operation by the gamekeepers to restore the old miners road in preparation for the imminent grouse-shooting season.

Right: in the wider area north of the Mossdale Mine we found an enormous boulder field or berm deposited by flood waters coming down Mossdale and also down an un-named gully shown below.

Left: The Mossdale shooting hut (NGR 0157 6975) and footbridge as we saw it. According to the gamekeeper, water levels were nearly to the top of the shooting hut lower doors, and the footbridge was completely submerged under a 200m wide river.

Right: large quantities of debris came down this un-named gully but much of it was removed by the greater force of the Mossdale Beck.

Left: Higher up Mossdale Beck, (NGR 0225 7100), the strand line is very prominent on the western (left) bank showing that the flood level in this vicinity was extremely high and stretched right across the rush floored valley to a width of some 30m or so.

Right: a moorland grip close to the adjacent image, has been deeply eroded out by the flood.

Around Kettlewell

Images from John Cordingley, Paul Smith, Richard Gibson and Anna Craven.

Left: John Cordingley's photograph of Park Gill near Park Rash on the morning of July 21. Note the strand line high on the left bank.

Right: Paul Smith's photograph of the severely endangered Providence Pot entrance, August 22, 2014.

Left: Richard Gibson and Simon Beck chanced to visit Park Rash on evening of July 20, having no knowledge of what had been taking place. They were astonished to find the Park Gill Beck in full flood whilst the Cam Gill Beck was absolutely normal.

Photo: Richard Gibson, July 20.

Right:

They followed the beck up to the Park Gill footbridge where the Park Gill Beck under the bridge was at a normal level.

Photo: Richard Gibson, July 20.

Left: the main flow of the beck showing higher strand lines on the far bank. ,

Photo: Richard Gibson: July 20 2243h.

Right:

A very large proportion of the flood waters came from the Dow Cave resurgences but at least as much came down Caseker Gill as seen on the extreme left of the image. Note the strand line lower right well above the present water level.

Photo: Richard Gibson, July 20.

Left: Anna Craven took these photographs from near her home in Kettlewell on the day of the cloudburst.

Right:

This photograph shows the beck much as described by others - "liquid mud".

Photos: Anna Craven, Kettlewell, July 20, 2014.

Around Hunterstones-Coverhead

Images from the author's collection January 8, 2015.

Left: The only obvious indications of the cloudburst seen in the Nidd Heads area was a sizeable landslip at approx 0050 7480 near Stone Head Top.

Right:

Further effects of cloudburst were sought around the northern and westerly areas of Great Whernside. From some distance away, what appeared to be a massive bog-burst could be seen near Slape Gill Shaw at 00862 76847. An area of two - three hectares of heather and peat had been thrown up in heaps leaving exposed the bare glacial clay.

Left: This moorland is privately owned but classed as 'Open Access' so we took the opportunity of reaching the 'bogburst' by following a shooting road across the moor.

Right: What we found was an astonishing sight - a classic, textbook, example of a 'bogburst'. Great masses of peat of up to 2m in depth had been thrown up leaving bare the 9000 year-old surface of glacial clay and till.

Left: peat thrown up by enormous quantities of water overwhelming 'pipes' of the type that often occur under a peat bog. This water would accumulate under the peat, itself bound together in a mass by overlying vegetation, until the sheer weight of water, under the force of gravity, forced up the peat in great masses. Free of the weight of peat the water would then be free to flow downhill shifting more and more masses until the energy of the water was dissipated. Little Whernside in the background.

Right: Richard gives a scale to the feature.

Left: Remnants of the ancient birch woodland that once covered the moorland is exposed near the base of the peat layer..

Right: A further equally extensive bog burst feature could be seen further down the fell side. Another such occurence was noted by Alan Dykes around the headwaters of Burn Gill.

Burn Gill, Coverhead

Images from the author's collection November 29, 2014.

A search for further evidence took us over Hunterstones down into Coverdale. There was no sign whatsoever in the numerous gills and beck feeding into the extensive upper Coverdale catchment until Burn Gill (left, right, and below) was reached (NGR 0127 7855). From the evidence of these masses of flood wash, the torrent down here from the catchment between Great Whernside and Little Whernside can only have been of truly enormous proportions.

.

Right: This photograph shows that the roadside wall and retaining stonework had been washed out over a distance of some 20m.

Dowber Gill

Images from the author's collection, November 19, 2014..

Left and right: Great masses of floodwash boulders and other debris in Dowber Gill

Left: Flood debris further up the gill as in the above images.

Right: A new streamway and cascade has been eroded out by the flood waters in this area.

Right: Some 60m below Providence Pot an enormous trench has been carved out of the pre-existing valley bottom sediments. As in several other locations previously unseen bed-rock has been exposed.

Left: A little further up the gill well-bedded grey limestone is now exposed.

Left: Near the head of the trench a substantial exposure of dolomitic limestone has been revealed.

Left: A confluence with an un-named beck close to the overlying millstone grit that shows absolutely no signs of having been subject to the sort of flood erosion seen in the main gill.

The same picture is seen much higher up the gill but whereas there is every indication of floodwaters coming down the north-easterly tributary of Hagg Dyke Gill there is no indication of flood waters having entered from the south easterly gill of Dowber Gill Wham.

Above: Great heaps of flood wash are common and, as the centre picture shows, the torrent falling over the millstone outcrop may have been as much as 5m wide and 2m deep.

Caseker Gill

Images from the author's collection December 19, 2014.

Left: Caseker Gill shows all the same indications of massive flood waters crashing down and displacing huge quantities of rock as seen in Dowber Gill.

Right: In the narrower steeper parts of Caseker Gill the flood waters have undercut unstable masses of glacial drift leaving landslips and slides at numerous points, three can be seen in this photograph.

Left: On the high terraced areas under the summit massif of Great Whernside the flood waters have been well spread out over relatively stable grassy areas. However, in many areas runnels of pebbles and slaty fragments have been washed out of the soil seen here on the left.

Right:A great mass of glacial drift has slipped away.

Hebden Gill

Images from the author's collection January 28, 2015.

Left: a walk up Hebden Gill soon revealed many indications of a recent major flood. Heaps of well washed cobbles and gravel were commonplace.

Right : a great mass of large boulders has been overturned immediately below the culvert through the embankment carrying the Duke's New Road over the moor to Cupola Corner.

.

Left: the dry valley below the Duke's New Road embankment illustrates the disruption to the valley floor.

Right : above the embankment the flood waters filled the old dam to the level of the overflow tunnel carrying old timbers that were left high above normal stream level after the waters subsided..

.

Left: The present stream feeds from Coalgrove Beck that showed no evidence of having seen a major flood.

Right : Coalgrove Beck does form a spectacular cascade as it falls over an outcrop of the Grassington Grit.

Blea Gill

Images from the author's collection February 25 and March 18, 2015.

Left, right and below: Blea Gill (sometimes known as Blow Beck) is one of the lesser known gills of the Grassington area. It is well hidden and access is restricted. Here again there is ample evidence of the cloudburst.

.

Right: Blea Gill also has the distinction of possessing one of the least known waterfalls in the Yorkshire Dales. It may be accessed from the Backstone Edge Lane footpath NGR 035631. Photo by Dave Milner.

.

Upstream from the waterfall, Blea Beck extends onto the vastness of Grassington Moor with some of the tributaries draining from the southern slopes of Meugher. In historic times all the natural watercourses of Grassington Moor were captured by the leadminers in a complex of dams, channels and leats. From these water could be led to the various treatment plants, most notably the Cupola Smelt Mill, in the south east corner of the moor. The purpose of the numerous dams was to store water for periods of drier weather when the natural water courses were likely to dry up. Among many others, the Duke's Watercourses, Upper and Lower, stretched over a distance in excess of seven miles.

The three Blea Beck Dams (see area sketch map above) were quite extensive with a total surface area of something in the order of ten acres (4ha). The embankments were breached long ago but the cloudburst of July 20, 2014, left a significant mark on this landscape. A bypass to the Blea Beck Dams known as Deep Cut seems to have escaped the floodwaters apart from the input from at least one moorland grip. The reason for this appears to be that the main streamway has previously been cut down to a lower level by erosion from earlier floods.

Left: the previously breached embankment of the lower Blea Beck Dam has been cut away by the floodwaters of the most recent flood.

Right : at the same location a minor fold in the shales of the country rocks is well exposed. Several other similar features may be seen nearby.

Left: immediately downstream of the previous images large quantities of flood-borne cobbles, boulders and shale fragments have been deposited.

Right : a moorland grip feeding Deep Cut has been greatly enlarged exposing a thickness of several metres of peat.

Left: immediately above the junction of Deep Cut and Blea Beck the great force of the floodwaters is clearly seen. Large boulders up to possibly a ton in weight have been dislodged.

Right : 400m upstream even greater effects of flood water erosion are visible. At this point it appears that some 5m or so of peat overlie drift deposits from the ice age. These two views look up to the southern flank of Meugher where it is assumed a major part of the cloudburst occurred.

Grassington Moor

Images from the author's collection March 25, 2015.

Left, the confluence of Sleet Moor Dyke and the upper extremities of Blea Beck (03760 68688 Alt. 426). A sheep fold stands at this junction and nearby are the ruins of an early shooting hut. A ten ton gritstone erratic also stands here. Sleet Moor Dyke drains a large part of the southern slopes of Meugher, a remote hill seen on the skyline on the extreme right of this image.

Right: a major input to the flood waters came down Sleet Moor Dyke.

.

.

Left, the upper part of a gritstone bed has been exposed nearby.

Right: as shown earlier the flood waters have carried down great amounts of debris and uplifted large boulders.

.

Right: Grassington Moor is noted for large shakeholes,often unconnected to any cave system. This one, like others in the vicinity, is most likely to be associated with the collapse of unseen mineral veins.

Right: also to be seen in this locality are the remains of a number of small stone buildings or shielings.

.

Left: the first indication of a change in the trend of the flood course. The main flow of flood waters came down Old Stones Dyke dyke, here trending towards Meugher, whilst the larger dyke, Straight Grainings, trending to the left (north-west) here, has carried a significantly smaller flow.

Right: Dave and Richard take a closer look.

Left and right: in this location, the underlying rocks comprise a thick bed of gritstone overlain by a thick bed of shale. The shale has been cut away by many generations of floods but the latest event has exacerbated the situation here in the drainage basin of Featherbed Moss leaving outliers of the shale standing above the surrounding landscape.

Left: close up of the shale bed, a sandy friable rock type, and, right: washed shale deposits show it to be of a very dark carbonaceous nature.

Left: Old Stones Dyke leads up onto Featherbed Moss again towards the southern flanks of Meugher.

Right : looking back down Old Stones Dyke gives an alternative aspect.

Left and right: Old Stones Dyke cuts down through a sandstone bed capping several metres of shale. A minor sandstone bed can be seen a metre or so below the top bed. The plank carries a small mammal trap.

Left and right: the overlying 3m or so of peat has been cut away as has the underlying original glacial boulder clay. The remants of the ancient silver birch woodland that once covered this landscape is revealed.

Left: Priests Tarn (02819 69526 Alt. 523) was the objective on this occasion but a little disappointing. A shallow hollow in the peat drains two or three minor drainage grips. Patches of snow lie on Great Whernside in the background.

Right : Great areas of the moor have been 'gripped' in recent times and this can only lead to a much faster runoff and consequently greater risk of flooding lower down. Meugher is visible centre horizon, 1.8km away.

Left: This un-named dyke carried a substantial flood to Black Edge Shake.

Right : Black Edge Shake (02323 68704 Alt. 484) is yet another of the mysterious vast shakeholes of Grassington Moor. It clearly takes large volumes of water but the underground water course remains a great mystery.

A record of some major historical and more recent flood events may be downloaded HERE

Any

shortcomings in the text are entirely my

own.

If you would like to get in touch or add information, there is an email

address:

mudinmyhair@btinternet.com

Steve Warren

Website

created by WarrenAssociates 2012

Website hosted by Tsohost

Copyright © Steve Warren 2012