Early days

The pages below are under development and will be updated on a regular basis as the various sections are completed.

Cycling Days

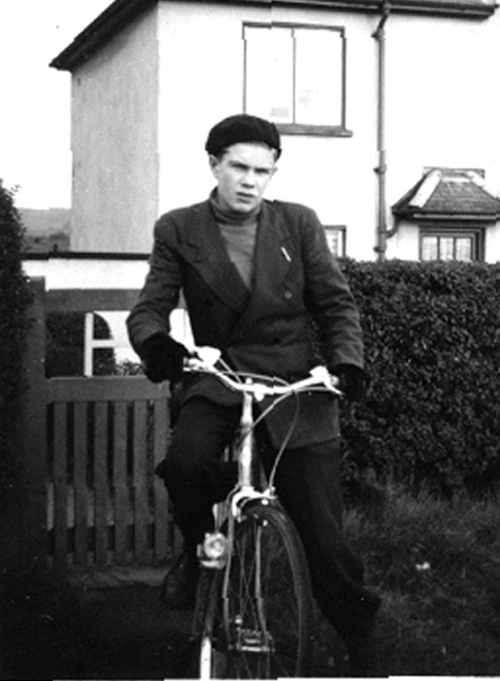

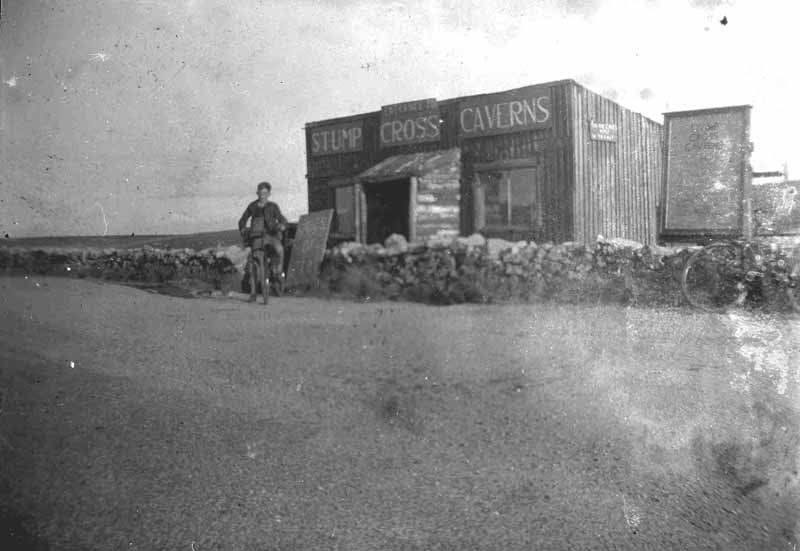

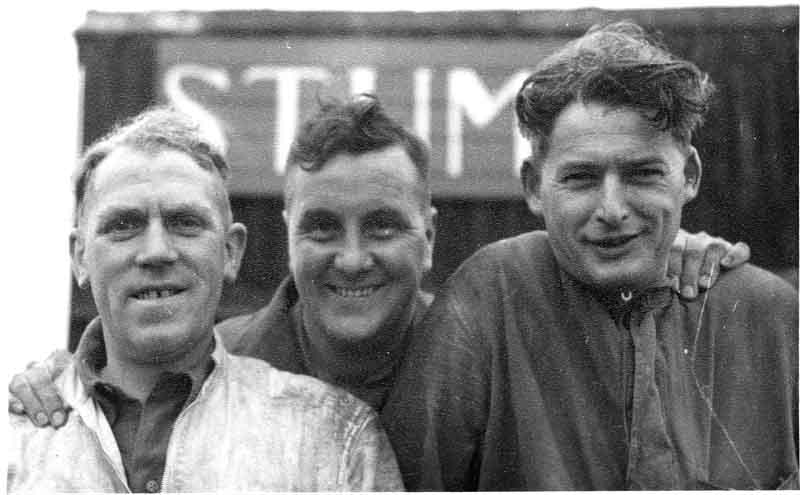

At the age of 15, I was the proud possessor of a brand new touring bicycle which my father had bought for me as a Christmas present (after a small pools win I think). With 'straight' handlebars, Sturmey-Archer three speed, 931 alloy frame, cable brakes and dynamo lighting, I could go anywhere. I thought nothing of cycling to my cousins in Bradford, from Middleton, for a Christmas party, and then cycling back late on a cold winter night. Now, having been to Stump Cross by car, my friend and I decided to go again, this time on our bikes, arriving there just as an elderly gentleman was taking a photograph of some other people. It was many years later that I discovered in the CPC records a copy of that picture – Albert Mitchell, Harry Pearcey and Stanley Baldwin were the subjects, on a CPC meet, and the photographer was probably John Mitchell. A few years later I got to know Albert Mitchell well and, of course, he was to have a significant influence on my life. Behind the group was the inelegant green wooden hut where George Gill ruled the roost, another character I would get to know well. The cave was very interesting but I wanted to see a real cave!

Setting off on my new bicycle in 1953. Photograph taken by my sister with our box Brownie. Processed by myself in the airing cupboard.

Left: Stump Cross c 1954. Friend Michael astride his cycle. My cycle leans against the wall to the right. Camera probably Brownie Box.

Right: Stump Cross c 1954. The party we saw at Stump Cross. Albert Mitchell, Stanley Baldwin and Harry Pearcey. This was probably the Craven Pothole Club meet of March 24, 1954 with John Greenwood as leader.

Giggleswick Scar

One of the earliest indepent outings I made was by bus to Giggleswick Scar with my cycling friend where we dismounted at the top of the hill and set off to explore all the caves shown in my new copy of Britain Underground. It was many years later that I learnt from Edgar Smith the origins of that book. Apparently, after a rescue of an exhausted caver at Sunset Hole, it became apparent to the police authorities that some proper organisation would be needed in the event of another such incident. Consequently a meeting was convened at Settle Police Station attended by Reg Hainsworth, Norman Thornber, Arnold Waterfall and others, all of whom had some knowledge of the problems. The biggest difficulty at the time was actually knowing the location of any particular cave or pothole should an incident occur and the police alerted.

Arnold had been keeping a record of all the caves and pots he knew of, and in fact he had created a card index similar to the ones he held for his extensive stamp and postcard collections. This he immediately passed on the Norman Thornber who had been nominated as recorder for the incipient Central Rescue Organisation. All this data was used in the compiling of the first comprehensive guide to caves and pots in the north of England. Accordingly, armed with this guide, we would be able to locate a number of caves which would easily be within our ability.

We carried each an ex-army knapsack containing a modified cycle lamp, an old jacket or jumper, some bits of rope, and our proudest possession, a thirty foot length of strong flexible steel Bowden cable, about 3/8 inch in diameter I think, with a loop at each end. Fastened to the outside of our packs we had our helmets, my friend’s was a standard British army WW2 helmet and mine was an American Army helmet, each fitted with a metal bracket to hold our lamps, just as we had seen in Casteret’s books and in Underground Adventure!

Our first call was to Buckhaw Brow Cave where a small short rift took no more than a few minutes to explore and merely whetted our appetites for something more adventurous. Our next location was Dangerous Cave which despite the menacing name seemed innocuous enough although a rope was deemed 'most advisable': but had we not taken that into account in our planning? Securing our fine wire rope to a tree, I slid down the fifteen or so to the bottom of the pit and looked around for the impressive stalagmite boss. My friend was happy to accept my word that there little to the place and declined an invitation to join me. Perhaps he could see what had escaped my notice: a wire rope is easy enough to descend but not nearly so easy to ascend. It was with some difficulty I escaped from Dangerous Cave having discovered that every single part of the body and every protubrance of rock must be brought into action when leaving a real cave.

My original copy of Britain Underground.

We

moved on to find the 30 yard long Kinsey Cave, a small short crawl to a

slightly larger section. It was whilst I was engaged in negotiating the

crawl with my friend in very close attendance that a piercing scream

came from behind.

"Spiders".

"The're everywhere".

" I'm off".

In fact the last couple of words were almost lost amongst the sounds of

scuffling, clattering of steel helmet on rock and scraping of boots.

I looked around, and yes, there were enormous red spiders crawling up

the walls and hanging from the roof. I had never had a problem with

spiders but neither had I any great affinity with them. I felt

distinctly uncomfortable and made an exit almost as fast as my friend

had. It was much later that I realised we had most likely been in the

adjacent Spider cave, a place noted for its population of red spiders.

We persevered in our explorations with brief looks at Staircase Cave

and Schoolboy Cave then carried on down the scars back to Settle for

the bus home.

After that episode my friend was reluctant to see another cave so I

started going out alone on my bicycle to Trollers Gill seeking Hell

Hole. I never found it which was just as well as I may well have got

into difficulties had I done so. It was about this time that my father

put me in touch with Arnold Waterfall as recounted below and my life in

caving got off on a sound footing.

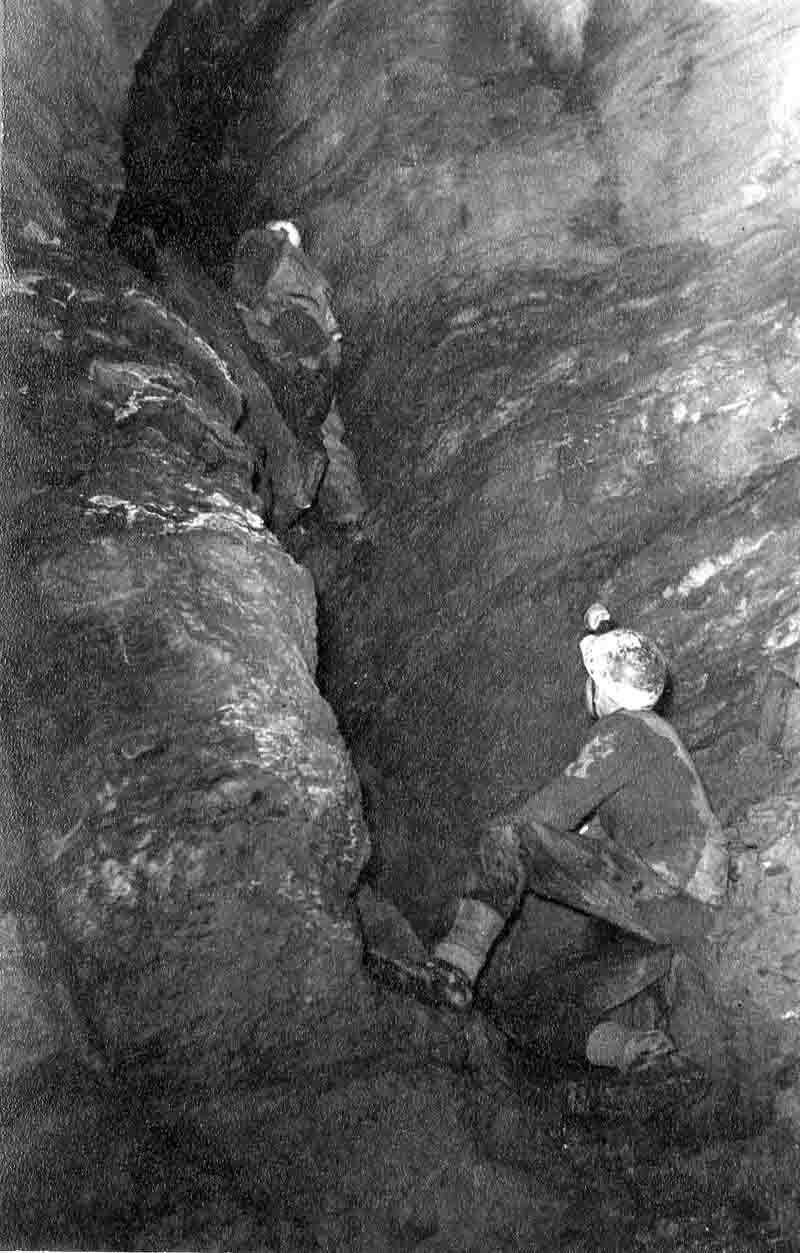

One of very few photographs showing the US army helmet, with a lamp fashioned from cycle lamp and a 9 volt bell battery, worn for the first few years of my caving.The higher figure is Dave Willis at that time a fellow member of the Craven Pothole Club. The photograph was taken by Arthur Hardy on the High-level Bypass in GB Cavern, during the Spring Bank Holiday Mendip Meet 1955.

Scordale

My first visit to the Northern Pennines was in 1954, with a new-found pal, Brin Powell, after we had met whilst pottering around Gaping Gill. Brin, who must have been no more than than fifteen years old at the time, greeted me with a cheery grin as I emerged from Rat Hole having been far enough along the tiny passage to peer over the edge of a drop of unknown depth. Many years were to elapse before I was to learn that the drop was the short cascade before the main drop, 340 feet (103m) down into Main Chamber. Earlier in the day I had poked my nose into Beck Head Passage, to the point where only immersion in the stream would allow further progress. Equipped with an early copy of Britain Underground, a handful of woollen jumpers, and a converted cycle lamp fixed to a ex-US army helmet, I was following an urge kindled by an unlikely comrade a year or so earlier. The unlikely friend had gone out of my life when it became apparent that his only real interest in caves and potholes was in reading about them.

His father, who appeared to make a living

farming mushrooms, had owned

a car, probably the only privately owned car in the vicinity. It was an

open top Singer, and he had taken the pair of us to the well known show

caves of Stump Cross Caverns and White Scar Cave. However, more

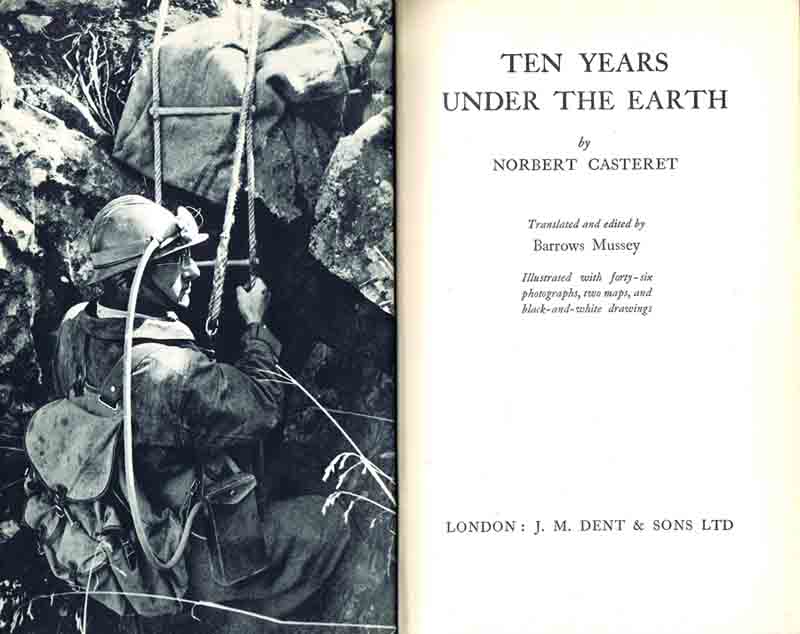

importantly, my unlikely friend had introduced me to Casteret's 'My

Caves', 'Ten Years under the Earth' and 'Cave Men New and Old'.

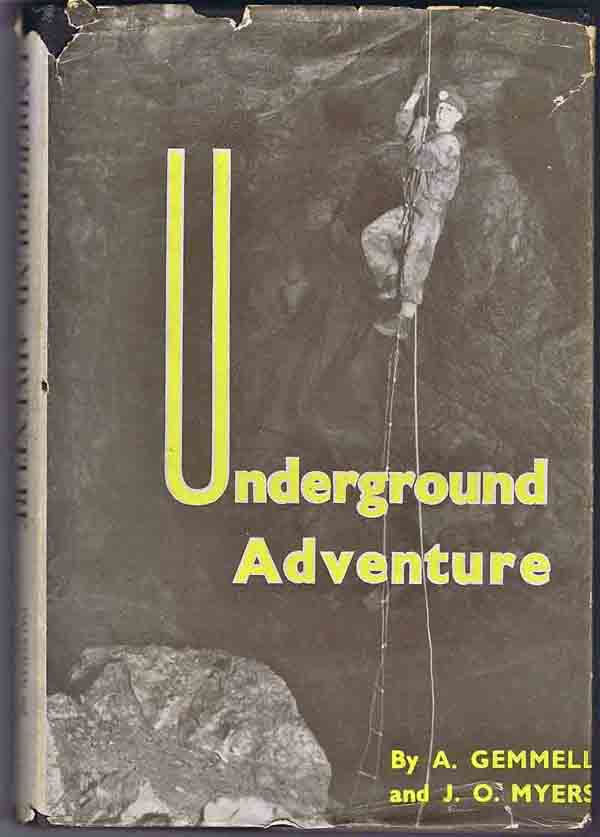

Moreover, he had shown me a copy of Gemmell and Myers 'Underground

Adventure', published in 1952. He had found them all in the local

library and they opened up a new world for me. Even then, with my

limited knowledge of caves and potholes, I knew that I wanted to spend

all my spare time exploring them, whatever they were and wherever they

were.

My unlikely friend was good company for a while as he was the only person in the neighbourhood who was prepared to join me in cycle rides to Timble, Plumpton Rocks, Keighley Gate, Beamsley and elsewhere, and, eventually to Stump Cross Caverns. On one memorable occasion, along with three or four other local kids, we cycled to Saltaire to spent a hot summer day swimming and diving on the canal locks quite close to Salts Mill. Our last outing together was to Giggleswick Scar as described earlier. I was fortunate in that my father, driver mechanic for the Middleton and Grassington Hospital Management Committee, occasionally transported members of the Board of the Committee between meetings at Otley, Middleton and Grassington in a large and quite ancient Austin saloon with extra fold down seats inside so it could carry seven or eight people. He knew quite well some of the Board members, including John Mitchell, at that time Editor of the Craven Herald and an early member of the Craven Pothole Club.

They would have much in common as my father was

at one time a very

strong walker. With the Bradford Harriers, and in the "heel-and-toe'

style, he had done the 'Whit Walk' between Bradford and Ilkley on many

occasions, and for a diversion now and then turned round walked back

the other way. They had been known to walk from Bradford to Settle for

a dance and back again next day and they had certainly walked to

Buckhaw Brow to watch the eclipse of 1926 because he talked about it.

He knew something about the Dales too as we had photographs of him at

Buttertubs, probably in the 1920's. After the war years we were quite

hard up as a family but we did have an uncle who owned a car and very

occasionally my father was able to borrow one.

Filey c1951

Enjoying Gordale with my two sisters round about 1947

Click on pictures for larger view: use back arrow for return

We

had been taken to Gordale on one occasion and later, as a contrast, my

uncle took me to Butlins at Pwllheli for a week. The most memorable

part of the week was the journey through the mountains of Snowdonia.

Another wonderful experience was being taken to Butlins at Filey for a

week, accompanied by my two aunts, the younger of which, my unattached

'Mad Aunt', enjoyed nothing more than travelling around. Thanks to her

we spent most of our time at Thornwick Bay, on Filey Brig, and on the

cliffs round about.

Thus, it was recommended by John Mitchell that I call on Arnold Waterfall who, with his brother Sydney, owned a newsagent and stationers shop at 10 Sheep Street, Skipton. With no more ado I got on my bike and cycled over to Skipton the following Saturday afternoon to meet one of the most accommodating persons it has ever been my pleasure to know. Arnold was at that time Secretary of the Craven Pothole Club and a veritable mine of information on all matters pertaining to caves and potholes. Arnold became a very close friend and confidant from that day until he died in 1990. It so happened that, the very next weekend, there was a Meet at Dow Cave, to which I was cordially invited. I was urged to get in touch with some Ilkley members of the Club who may be able to help with transport at least as far as Skipton where I could catch the Club Bus which would take members up to the proposed venue near Kettlewell. Arnold showed me into the wonderful map-room created by his brother Sydney, with which I was to become quite familiar. In fact within a few years I was to become custodian of the Club Records and Library stored there at the time. Before I left, Arnold sold me a copy of the Craven Pothole Journal, Volume 1, Number 2, 1950, for six shillings (30p) which was about as much as I could afford at the time. On the way home I stopped, parked my cycle in a ditch, and sat on a wall by Chelker Reservoir and read it all quite avidly. One of the articles which stuck in my mind was about a Meet at Gaping Gill by Brian Hartley.

It

was this item that had resulted in my visit to Gaping Gill and meeting

up with Brin. Herbert Rhodes was my first port of call back in Ilkley

but, unfortunately, his caving days were coming to a close and he was

unable to help with transport. Herbert was a prominent figure in local

photographic circles and in his caving days he produced many superb

photographs all made with a plate camera and, usually, magnesium flash,

in Gaping Gill and Clapham Cave, now known as Ingleborough Cave.

Herbert did take time to show me some cave photographs and he did

mention a new cave passage near Kettlewell. The new cave was the

Caseker Gill Extension to Dow Cave, first entered by John Hobson on

June 28, 1953, via the original terminal choke which became known as

Hobson's Choice. Shortly after this John emigrated to New Zealand where

he established a reputation as a cave explorer of some note. My next

call was on Nigel Nicholson who lived in an apartment in a large house

almost on the edge of Ilkley Moor, terrain I had come to know well

during the war years as my mother had frequently taken us up there on a

fine day. Nigel's interest in caving was waning but he did own a car, a

Morris Minor I think, and astonishingly, he did offer to take me to

Skipton on the following Sunday, for 9.30, to catch the Club bus. This

small act of kindness was something I have never forgotten. I later

found that Nigel was something of a fell runner, before such activities

became the vogue, and he was one of the first people to complete a

double round of the Three Peaks, on the Easter weekend of 1956, in a

few minutes over 21 hours. Our paths may well have crossed on that

weekend as I was encamped behind the Station inn at Ribblehead, and

over the weekend I spent many hours in the company of Harry Sanderson

and John Normington walking around the fells nearby.

Ribblehead c 1955 or 56 l-r Eric Burns, Harry Sanderson, Edna Crunden, Tony Wass, John Normington; Bert Lynch in window. Photo from colour slide by Bob Crunden.

Haytime at Home Farm, Middleton. c1951.

However

to return to the main thread of this story, Brin persuaded me that, as

we had a long Bank Holiday weekend in front of us, the fourteen

shillings required for the return train fare from Settle to Appleby

could be well spent taking us for a weekend in Scordale. Apart from the

train and a bus between Clapham and Settle, the rest of the journey

would be on foot, complete with our scruffy camping gear and wretched

caving rags. We were following in the footsteps of the Brindles, Dennis

and Norman, even then well known as cave finders, with whom Brin had

previously spent a weekend up there. They were probably the first to

spot the rising at Amber Hill and then dig at the sink in Swindale a

mile or so away.

At times Brin talked about a cave passage with

waist-deep water which I learnt later was the newly discovered Dowber

Gill Passage. From those exploits he knew rather more about caving and

camping than I did but I had the advantage of having spent most of my

spare time and all of my school holidays on a local farm and I had

plenty of experience of fending for myself. By the age of fourteen I

not only knew how to tie a load of hay onto a trailer but I was a

competent tractor driver too.

Apart from that, having lived in the countryside from the age of eight,

I had enjoyed free rein to wander the fields and moors around Ilkley.

As a little gang, a handful of pals from the Middleton district and

myself, we spent much of our free time on ancient bicycles hurtling

through the woods and over the moors, often following close behind

local motor cycle trials. A special treat was to follow the Ilkley

Grand National, a strenuous trial around Langbar, Beamsley, Bolton

Abbey and Denton after which we would arrive home exhausted, sodden wet

through and totally plastered in mud. We were 'mountain-biking' several

decades before the sport was invented in Marin County, California, in

the 1970s. Just what our parents thought of all this escapes memory but

they must have been content to see us home safe, sound and gloriously

happy. It was, perhaps, a great preparation for a life in the wet muddy

caves of the Yorkshire Dales anyway. Otherwise most of my spare time

was spent around the farm just up the road from our house.

But the long

walk from Appleby station was under a scorching sun and, along the way,

naturally, we called at the village shop in Hilton to replenish our

meagre rations.

Brin and I set up camp on a wonderful hot

summer weekend high up on the

flat green turf of a mine heap at the very head of Scordale. After

settling in we ventured into some of the defunct mine workings,

Jacque's Level was one to which Brin could put a name, having little

regard, or knowledge even, of the many hazards they could present to

the unwary.

Between us we managed to survive, largely on sausage

butties, as I remember it. Our sustenance at that time often comprised

chipolata sausage, always referred to as 'Moriarties', fried and

sandwiched in bread thickly plastered with butter which dripped and

dribbled down our chins and around our fingers as we ate. The fat left

in the pan was used to oil our boots and, towards the end of a weekend,

any bread left over was fried in the remaining fat together with any

unused butter in a frying pan made red hot over a roaring stove until

black smoke filled the air. Fried to the brown-side-of-black, rather

than the black-side-of-brown, the contents of the frying pan were

plastered with sugar, and folded into a sandwich the deliciousness of

which remains in my memory to this day. A few years later this

ritualistic offering became known as the 'Darnbrook Butty'. We probably

had a few tins of beans and Irish Stew too.

On this occasion we did

most of our cooking on a open fire kindled from old mine timbers in an

massive antiquated iron grill, a relic from the mining days. Brin

proudly announced that Norman had carried the grill up from the valley

bottom on his back. Considering that it must have weighed nearly two

hundredweight, I too was suitably impressed with this mythical

character I had yet to meet and learn about. Our water came from the

entrance to the Horse Level, a few yards away from our camp. On our

return to the Dales we were to spend many a weekend camping in Dowber

Gill with Norman and with Brin's brother, Bob, together with Arthur

Hardy, Jack Wakefield and others. Bob became one of my closest friends

later in life. That all resulted in the discovery of Providence Pot

and, later, the first epic 'through trip' by Norman and Bob but by then

Brin had left our team and I never heard of him again until I was told

some years ago that he had died at the early age of 51 during a tour of

the Mediterranean as a merchant seaman.

"A

mythical character I had yet to meet and learn about"

Norman Brindle in Swindale: early 1950s: photographer unknown: source

ACW records

Any

shortcomings in the text are entirely my own.

If you would like to get in touch or add information, there is an email

address:

mudinmyhair@btinternet.com

Steve Warren

Website

created by WarrenAssociates 2012

Website hosted by Tsohost

Copyright © Steve Warren 2012